November 12, 2022

By Z Paige L’Erario, MD, NYS CRPA/CPS-provisional and Holly Fancher, LMSW, MSEd

Originally Posted in Social Work Today; Vol. 22, No.4, P.22

“This case study examines a field intern’s right to refuse clinical services to a sexual or gender minority client.“

Discriminatory behavior against sexual and gender minority clients is often more a systemic issue than an individual one. Social workers have professional and ethical duties and obligations to provide culturally competent clinical services to every client, regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity. However, there are several states currently introducing anti-LGBTQ legislation, which raises a question about the ways in which a supervisor may handle a social work student who refuses to provide clinical services to a sexual or gender minority client.

Refusal by a field intern to provide services to a sexual or gender minority client should be viewed through the lens of a person-in-environment, which requires a biopsychosocial approach to fully address the issue. Techniques for approaching a social worker who refuses to work with a client based on their sexual orientation or gender identity include the following:

• engaging, assessing readiness for change, and motivating social work students to learn more about culturally competent care for sexual and gender minorities;

- pairing the student with a more experienced social worker to observe culturally competent practice;

- providing the student access to sensitivity and diversity training;

- increasing supervision sessions to include discussions of values, stereotypes, and oppression that currently impact social work practice and skills to learn to address gaps in culturally competent practice; and

- reassigning the student to an agency where their personal beliefs and institutional values will not be in conflict.

Case Study

The following case study has been presented within the Fordham Graduate School of Social Service’s online Master of Social Work curriculum:

At Field Agency X, a social work intern refuses to provide clinical services to their assigned client due to the client’s perceived or confirmed gender identity or sexual orientation. For example, the intern is assigned the case of a same-sex couple who wish to begin a family. They seek support and advisement on options for fertility treatments. However, the intern demands the case be reassigned, citing religious and moral objections. In essence, the intern has requested not to engage diversity and difference in practice, one of the core competencies of social work education.

How should a field supervisor, who oversees social work students, address this situation? To get a handle on the matter, the following questions should be considered:

- Can a social worker refuse service to someone solely because of their identity or the way they look or act? What if the client had been refused care because they were a racial minority?

- Can a social work student be allowed to graduate if they refuse to learn about or cannot adopt the core competencies of social work practice, such as the biological diversity of gender, sexuality, and identity formation? Should personal beliefs or lack of cultural competency be allowed as a reason to refuse service to a client?

- Should we allow a social work student to practice in ways contrary to professional and ethical standards?

Case Study Discussion

In answering these questions, it’s imperative to consider the ethical, professional, and legal obligations that govern a social worker’s practice. Professional social workers have a foremost “duty of care” in which they are “legally obligated to provide a reasonable standard of care in delivering social work services.”1 Furthermore, “clients have a right to expect that [social workers] will discharge professional responsibilities in a competent manner.”1

Excluding clients on the explicit basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity disregards this duty of care and is in opposition to the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the NASW’s Code of Ethics.2,3 Furthermore, discrimination involving medically necessary health care needs based on sexual orientation or gender identity is federally illegal, with additional protections against discrimination in public accommodations in many states and localities.4-6

Therefore, this social work intern’s refusal to treat a client due to their sexual orientation or gender identity raises multiple ethical concerns and violations of social work practice policy.

Social Work Code of Ethics

NASW identifies social work’s core values in the preamble to its Code of Ethics. Two core values (social justice and dignity) are violated when a social worker refuses to treat a client on the sole basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity. The preamble suggests that “the primary mission of the social work profession is to enhance human well-being and help meet the basic human needs of all people, with particular attention to the needs and empowerment of people who are vulnerable, oppressed, and living in poverty.” Therefore, social workers have an intrinsic professional responsibility to care for those of sexual or gender minority status.

In the Ethical Standards Section 1.05 of the Code of Ethics, social workers are described to have specific ethical responsibilities to clients: “Social workers should demonstrate understanding of culture and its function in human behavior and society, recognizing the strengths that exist in all cultures.”

Professional ethics dictate that students develop and demonstrate cultural awareness and humility by engaging in serious and critical self-reflection, defined as understanding their own biases and engaging in self-correction. It is essential that those working with sexual and gender minorities be able to fulfill their professional responsibilities outlined in the Code of Ethics by demonstrating a working knowledge of social diversity and the nature of oppression, which applies to sexual orientation and gender identity. At the very least, social work students should remain open to learning more about queer culture.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights applies to all people, including sexual and gender minorities. Article 1 specifically states that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Social workers should not be allowed to purposefully exclude clients based on their minority status; that kind of personal decision does not fulfill either their professional responsibilities or the basic human rights defined in the Universal Declaration.

Article 16 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights reads, “Men and women of full age … have the right to marry and to found a family.” Social workers must not discriminate against those who choose to do so based on personal beliefs. Instead, they should fulfill their professional responsibilities as outlined in the Code of Ethics.

Legal Protections Against Clinical and Public Service Discrimination

In the case study, the intern’s choice to exclude clients from clinical services based on their sexual orientation or gender identity may be illegal, depending on the intern’s practice location and the reimbursement and funding sources. Health care can be considered a segment of social work services, a part of the clinical support services that clients may receive at their social work agencies. There are federal protections against health care discrimination for sexual and gender minority clients in Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act, which established broad civil rights protections in health care, barring discrimination based on sex (including sexual orientation and gender identity) in “any health program or activity” that receives federal financial assistance.6

This policy was upheld recently by the Department of Health and Human Services in the Biden Administration.6 There are additional health care and public accommodations nondiscrimination laws that would apply at the state and local level.4,5 However, recent legislation introduced in several states has attempted to criminally ban transgender adolescents from receiving medically necessary gender-affirming care, which may embolden agencies and their representatives from refusing clinical services related to their sexual and gender minority clients.7

Professional Development Plan

In the best-case scenario, this intern is responding to their client without the ability to separate their professional responsibilities from their personal beliefs. In other words, the intern is unable to practice cultural awareness or incorporate sensitivity and diversity into their practice. In the worst-case scenario, the intern is acting unethically, unprofessionally, and possibly illegally.

Ethics flow from values and can be thought of as values in action. In the case study, by refusing to work with a same-sex couple, the intern is choosing their personal beliefs over their professional obligations, which means their actions amount to unethical practice. As the field instructor and intern work collaboratively to search for ways to resolve the conflict between their personal beliefs and professional obligations, it is hoped the intern learns to be comfortable with discomfort.

The supervisor should recognize that the agency’s staff are entitled to their personal beliefs, but these beliefs cannot be incorporated into their practice at the expense of their clients. Still, changing attitudes and behaviors takes time, effort, a flexible perspective, patience, persistence, and coordinated planning. A supervisor should be ready to support an intern going through such changes.

In the short term, the best way to serve these clients is to reassign them to a more experienced social worker. Outside of a research study with informed consent, it is not acceptable to use this client as part of the intern’s professional development.

After reassigning this client to another social worker, assessing the intern’s readiness for change is important. Using a 1 to 10 scale outlining “readiness for change” may be helpful to better comprehend this individual’s starting point—their motivations, perspectives, and understanding of the situation.8

Dealing with values is central to social work practice. As an inexperienced professional, the intern needs to learn they belong to both their individual value system and the value system governing the profession of social work practice. As a person also belonging to their environment, the student is defined by both. The intern’s attitudes and behavior are shaped by the complex interactions of their environment in the same way as are their clients.

By understanding that everyone involved in the situation belongs to systems composed of interrelated and interdependent parts, the supervisor—using ethics as their practice framework—must find ways to support the intern while they grow into a social worker. A good starting point would be to ask the intern: “How open are you to learning more about sexual and gender minorities?”

A biopsychosocial assessment means a nonjudgmental exploration of the intern’s capacity to nonjudgmentally respond to the concerns, needs, and problems of sexual and gender minority clients. Depending on the student’s answer, the supervisor can ascertain where the intern is in the process of addressing their implicit biases and their desire to learn more about queer culture.

The supervisor is ultimately responsible for providing ethical clinical services for all clients seeking services at that agency. While the profession undoubtedly wants interns to succeed, there needs to be a timeframe established for professional improvement. The agency’s mission cannot be indefinitely sacrificed for one staff member, but nonjudgmental practice dictates that goals be created and a contract established with the intern in the same manner they would be with any client. Ethical social work practice is not just about clients; supervisors must also adhere to the same values and standards.

The supervisor should earnestly attempt to develop awareness and empathy by setting up additional clinical sessions with the intern to discuss the following:

- how the intern’s attitudes and beliefs about sexual and gender minorities influence their capacity to practice social work;

- the historical and current stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and oppression impacting sexual and gender minorities; and

- the skills that the intern could use when providing services in an ethical manner, including engagement, empathy, cultural competency, active listening, and reflection.

Supervisors may want to consider having the intern shadow more experienced social workers to see ethical practice firsthand. Keep in mind that such a strategy requires the client’s consent. Additionally, the supervisor could help the intern enroll in culturally competent practice trainings to develop diversity practice skills.

If, however, the intern found the discontinuity and conflict between their personal and professional selves too much to handle, it may be time to acknowledge that they are not a good fit for a secular agency. One option for the intern would be to consider working for a faith-based agency that is more consistent with their religious or moral perspective.

Once it becomes clear that an individual needs a different kind of working environment, it is important that supervisors do not fall into unprofessional practice, displaying negative behavior themselves by thinking about or treating the intern in disparaging or derogatory ways. All relevant parties practicing social work should use the theories and skills taught in everyday environments.

Often, personal vs professional difficulties reflect a systemic issue more than an individual one. What is considered right and wrong in terms of behavior is always rooted in the social environment, and it is still likely that this social worker will be able to provide meaningful services for other clients whose social and religious upbringing is more aligned with their own, thus integrating micro and macro practice lenses. A nonjudgmental approach requires that supervisors also apply a strength-based model toward interns, clients, and the larger agency. Hopefully, this social work intern will be able to reconsider their perspective and practice. Sometimes it is hard to know exactly where people exist along the change continuum, and it often takes several cycles for the planted seeds to produce new awareness and understanding.

Revisiting the Discussion Questions

Embedded in social service education, competencies, values, ethics, and practice is the tenet that no one should be refused service based on a historically oppressed identity. If such discriminatory behaviors arise, steadfast interventions should encompass the person-in-environment and systems perspectives. Agencies should also engage individuals displaying cultural insensitivity with a motivational interviewing approach, as well as provide dedicated inclusivity training and positive role modeling.

For social workers, it would be contrary to professional duties and responsibilities to remain intentionally ignorant of diverse cultures and refuse services on this basis. Social work students continually need to reach outside their comfort zones to learn culturally inclusive practices for all clients.

Supervisors must lead by example and commit to a high standard of ethical and inclusive conduct for both themselves and students.

— Z Paige Lerario, MD, NYS CRPA/CPS-provisional, is a neurologist and transgender activist. They are a graduate student of social service at Fordham University.

— Holly Fancher, LMSW, MSEd, holds two master’s degrees, one in social work and one in higher education. She teaches at Fordham University in the online MSW program and is working on her PhD in social welfare at the CUNY Graduate Center.

References

1. Cournoyer BR. The Social Work Skills Workbook. 8th ed. Cengage Learning; 2017.

2. Universal declaration of human rights. United Nations website. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights. Accessed August 17, 2021.

3. Code of ethics. National Association of Social Workers website. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English. Accessed April 13, 2022.

4. New York State Division of Human Rights. New Yorkers Are Protected From Gender Identity Discrimination by Hospitals. https://dhr.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2022/05/dhr_gender_identity_handout.pdf

5. Nondiscrimination laws. Movement Advancement Project website. https://www.lgbtmap.org/nondiscrimination-laws. Accessed April 13, 2022.

6. Shear MD, Sanger-Katz M. Biden administration restores rights for transgender patients. The New York Times. May 10, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/10/us/politics/biden-transgender-patient-protections.html. Accessed October 1, 2021.

7. Turban JL, Kraschel KL, Cohen IG. Legislation to criminalize gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. JAMA. 2021;325(22):2251-2252.

8. Rollnick S, Heather N, Gold R, Hall W. Development of a short “readiness to change” questionnaire for use in brief, opportunistic interventions among excessive drinkers. Addiction. 1992;87(5):743-754.

Disclosures: Lerario serves on the editorial board of Neurology: Clinical Practice, has been hired as an expert witness for plaintiff by Weiss Law, and is the vice-chair of the LGBTQI section of the American Academy of Neurology. Fancher reports no financial disclosures relevant to the manuscript.

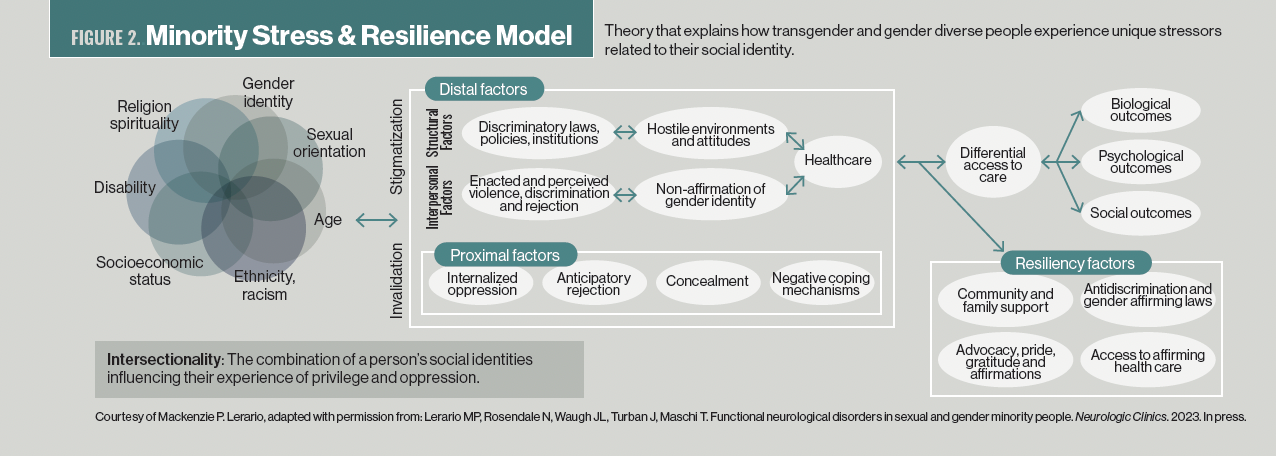

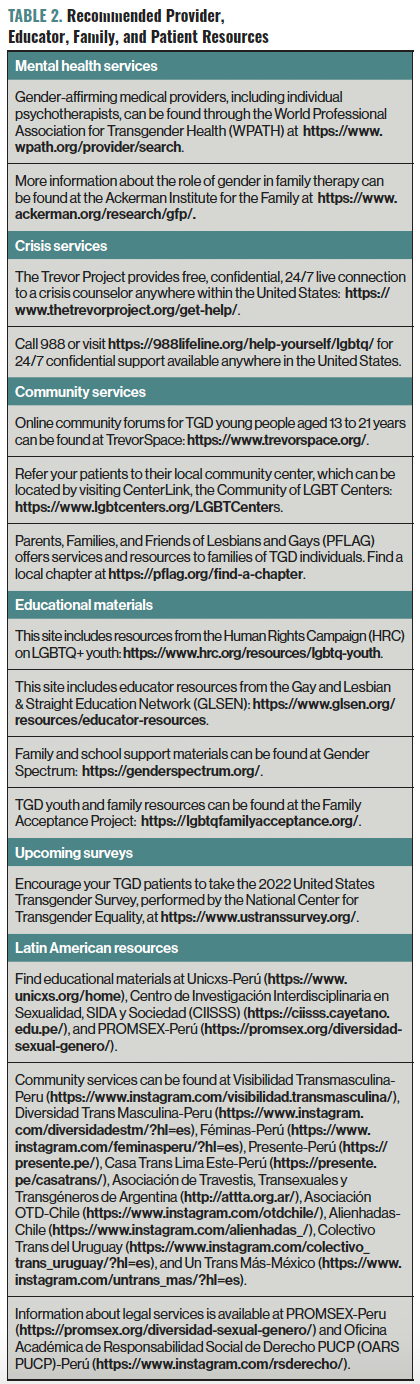

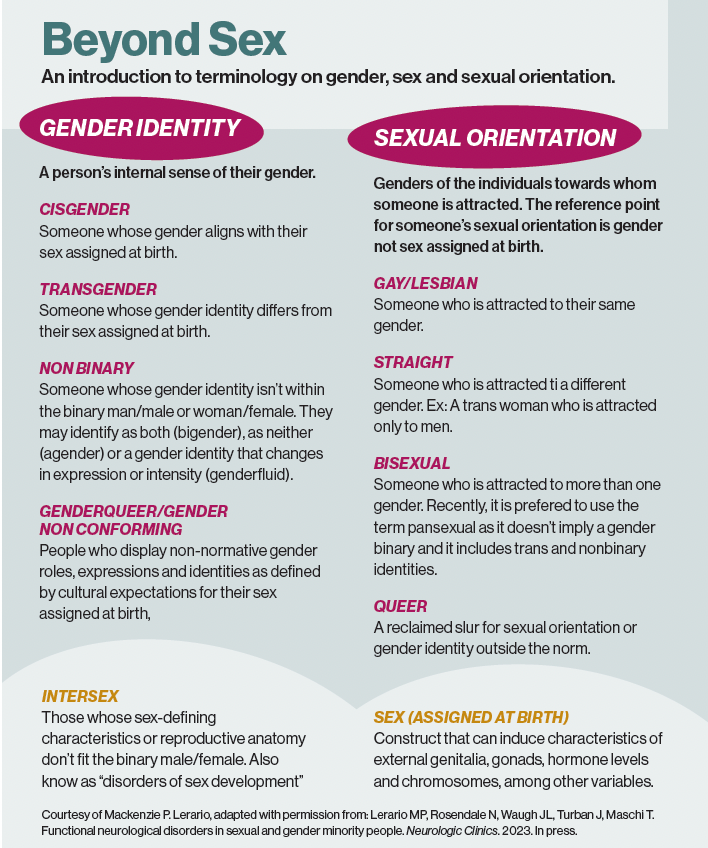

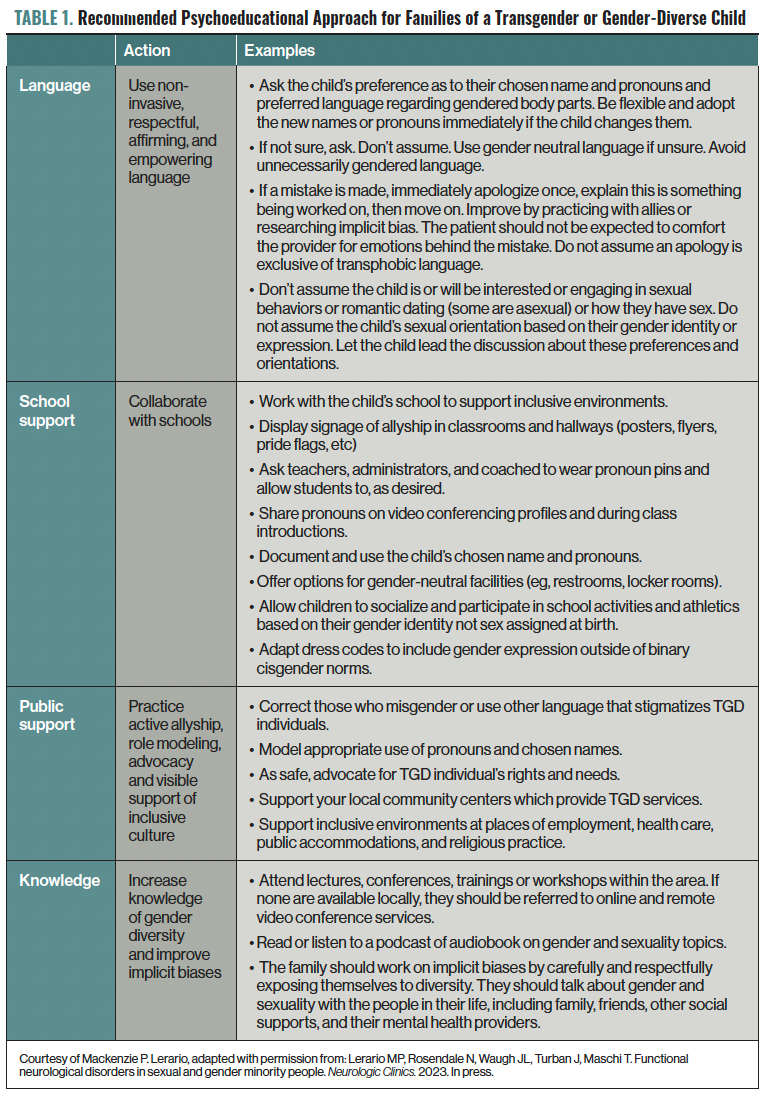

This is the Sidebar of the article

This is the Sidebar of the article

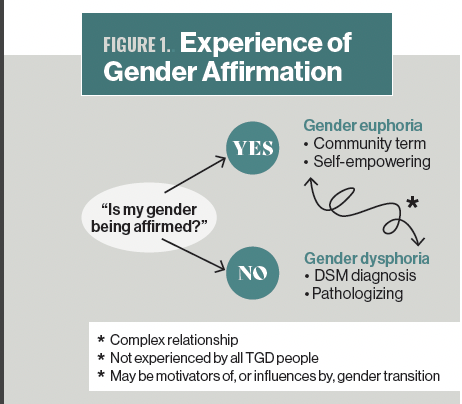

Figure 1. Experience of Gender Affirmation

Figure 1. Experience of Gender Affirmation