Affirming Evidence-Based Care for Young Patients Who Are Transgender or Gender Diverse

SPECIAL REPORT: PSYCHOEDUCATION

The data is clear: We should expect an increasing number of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) youth presenting to our practices over the coming years.1 We must ask ourselves: Are we prepared to treat these patients and their families with the most affirming, evidence-based treatment available?2

Case Example

For discussion purposes, consider a prototypical case of “Bar,” an 11-year-old child who presents to your office accompanied by his parents. Bar was assigned female at birth but recently began identifying with “he/him” pronouns; he is scared to face impending puberty. Bar’s father informs you that he is afraid Bar will be “bullied for being gay.”

Supporting the Patient and Their Family

Recent qualitative studies suggest that the caregivers’ response and adjustment to their TGD child’s identity development is critical to the child’s mental health.3 An integrative family therapy approach should affirm and support the TGD child in an equal partnership between the caregivers and the child.4 Addressing attunement and attachment is important for the family system, as there is likely longstanding intergenerational trauma from adoption of rigid, binary gender norms.5 Families should prioritize building psychosocial support for, and affirming the gender identity of, the TGD child, rather than focus on worries like “Is this my fault?” “What went wrong?” or “Is this just a phase?” The family may express grief due to the loss of an expected future they associated with the assigned sex of a transitioning child.6

Distress tolerance and interpersonal relationship dynamics can be tested during a gender transition7; as a result, many with gender dysphoria may be misdiagnosed with personality disorders.8 Dialectical behavioral therapy is a good therapeutic option for these patients.9 It is important that group therapy options provide affirming environments for transgender group members. This includes the facilitator’s role modeling of appropriate usage of pronouns and chosen names during therapy sessions.

Disclosing a shared identity with a patient can aid the therapeutic alliance by displaying understanding and empathy for the patient’s experience, which can facilitate trust and reciprocity.10,11 It is vital that providers reflect on whether self-disclosure is being done with the intent of improving patient care, and peer supervision around this can be of value.

Psychiatrists should model inclusive environments to their TGD patients within their offices and clinical spaces.12 Patients and their families should feel safe to give feedback to the psychiatrist when they fail to produce an affirming patient experience.2 In these situations, the administrative response should be transparent and timely, and it should address the root cause of the issue. Psychiatrists should collaborate and advocate with the family and other community and mental health professionals, such as school psychologists and counselors, to create affirming environments within the child’s home and school life.13 It is imperative that work with TGD patients involves ongoing feedback and participation from affected community members throughout the learning and healing process.14

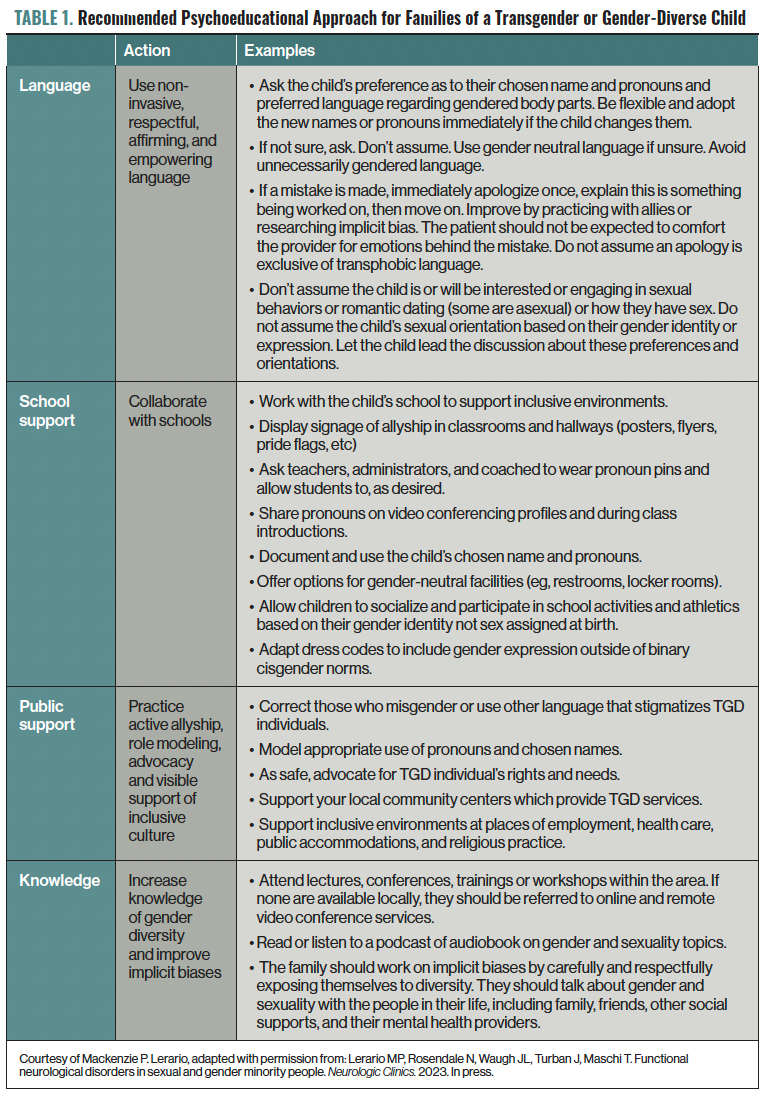

To create a more affirming environment for a TGD child, psychiatrists should collaborate with the family, school, and community. For example, using noninvasive and empowering language can be a great first step in establishing not only a good environment, but also a therapeutic alliance. See Table 1 for more information, and the Sidebar.

Psychiatric Terminology: Is the Field Doing Enough?

Gender Dysphoria and Its Significance in the TGD Community

Gender dysphoria is a term that originated within psychiatry. The DSM-5-TR defines gender dysphoria as “the psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity.” Gender euphoria is an accepted term used in the TGD community that recently entered the peer-reviewed literature.15 It is defined as a “joyful feeling of rightness” and the “powerfully positive emotions” that comes from one’s gender. See Figure 1 for more details on gender dysphoria and euphoria.

Gender dysphoria is caused by repeated exposure to gender-nonaffirming environments, which can result in higher rates of depression, anxiety, trauma and stress disorders, rumination, somatization, and suicidality in TGD individuals.16-21 The mismatch between a person’s self-identified gender and invalidating environments can occur within multiple domains, including online, home, school, athletic, employment, carceral, and health care settings.22-28 Access to affirming environments and health care improves mental health outcomes28-30; on the other hand, nonaffirming environments and barriers to health care increase disparities for TGD individuals.31,32 Due to recent attempts to criminalize evidence-based affirming health care for TGD individuals, psychiatrists should expect to see an increase in patients presenting with gender dysphoria in the near future.33

The Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Theory

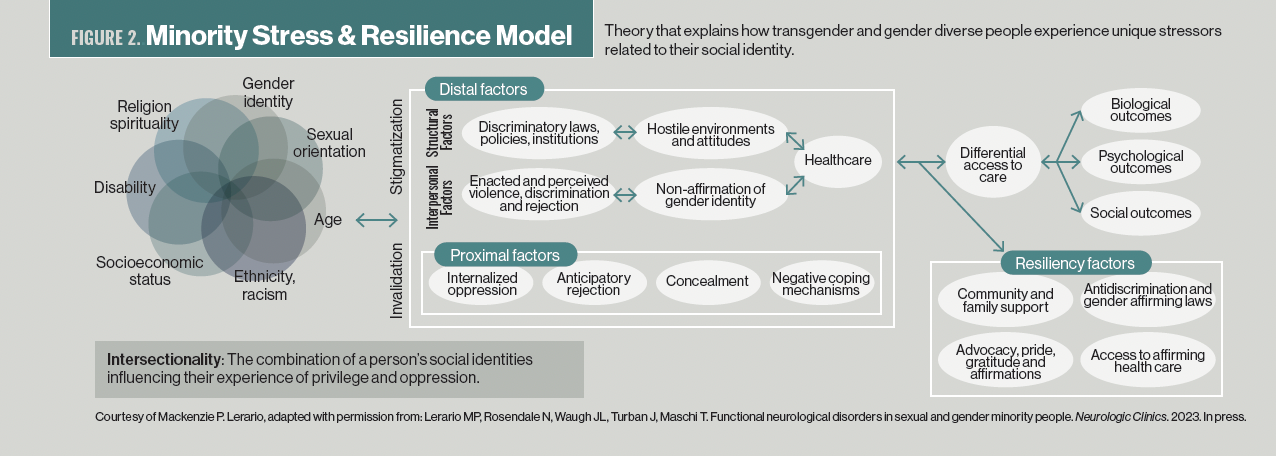

The Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Theory describes the disparate impact of risk and protective factors on the experience of internalized (proximal) and external (distal) oppression in TGD communities.34 These stress and resilience factors combine with other forms of social identity–based discrimination, such as racism and socioeconomic disadvantage. Taken together, this intersectionality is responsible for the structural pathways leading to systemic health care inequities experienced by TGD community members (ie, social determinants of health).35 Figure 2 provides more details on minority stress and resilience.

Minority stress models have been used to explain the increased risk for biological, psychological, and social health disparities observed in TGD communities. These biological factors include increased rates of cardiovascular disease and cancer-related outcomes, whereas psychological outcomes of minority stress include depression and suicidality.36-38 Among the TGD community, social disparities and structural disadvantages have been noted in increased rates of incarceration, housing instability, underinsurance, and risk behaviors, such as substance misuse as a negative coping mechanism.27,39-41

Figure 2 expands on this topic and gives examples of resilience, or protective factors, that moderate the effect of minority stress.42 Resilience factors include methods to create systemic and structural changes that increase the psychosocial support and affirming environments available to TGD individuals.43 Additionally, TGD individuals can learn skills such as community building, advocacy, role modeling, and other expressions of pride, self-worth, and self-acceptance.

Conclusion of Case Example

You diagnose Barr with gender dysphoria and provide supportive psychotherapy throughout the social transition process. You present Barr with information regarding his local community center, where Barr becomes active in peer support and social activities. You provide educational resources to Barr’s parents, who join their local PFLAG (Parents, Families, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) chapter to speak with other parents of TGD children. You discuss the changes in pronouns with Barr’s school psychologist and work with school administration to help develop strategies for Barr to express his gender authentically within the school’s policies.

After a year of treatment, although Barr feels more confident in his masculine gender expression, he reports ongoing depression due to expected changes with puberty. As a result, you refer Barr and his parents to a gender-affirming endocrinologist to discuss options regarding potential puberty suppression and timing.

Concluding Thoughts

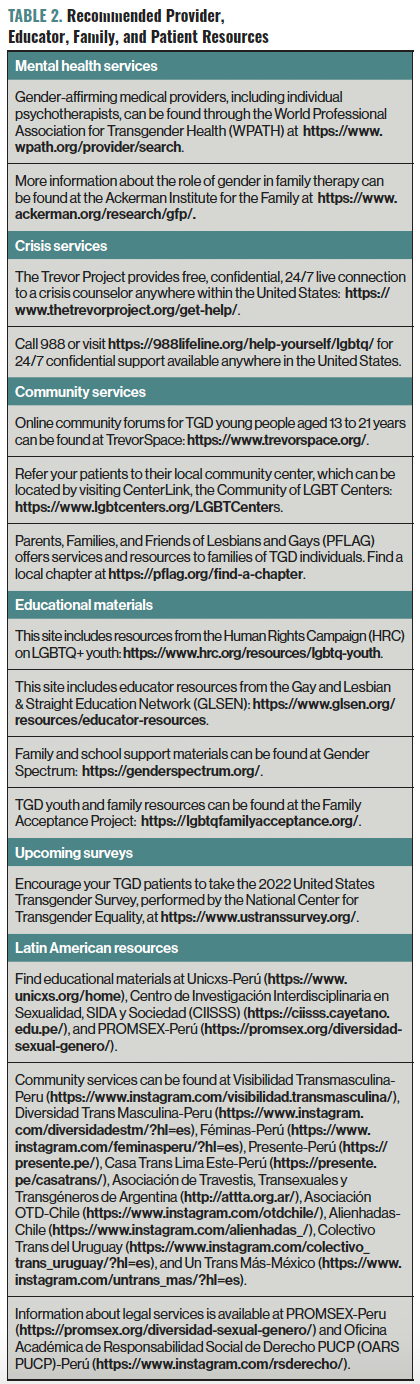

Psychiatrists are in a unique position to empower their patients by recognizing and addressing key issues surrounding gender and sexuality. This includes the use of sensitive and inclusive language and assisting the field in adapting to ongoing evolution of community standards of care. Similarly, it is important to integrate transition and resocialization efforts with the patient’s family, community centers, and school professionals. Table 2 provides a list of potential resources to help in this endeavor. Together, we can work to provide affirmative and evidence-based care for all youth, whether or not they identify within the gender binary.

Originally Published November 29, 2022 in:

“Psychiatrists are in a unique position to empower their patients by recognizing and addressing key issues surrounding gender and sexuality.”

This is the Sidebar of the article

Table 1. Recommended Psychoeducational Approach for Families of a Transgender or Gender-Diverse Child

Figure 1. Experience of Gender Affirmation

Figure 2. Minority Stress & Resilience Model

Table 2. Recommended Provider, Educator, Family, and Patient Resources

References

1. Jones JM. LGBT identification in U.S. ticks up to 7.1%. Gallup. February 17, 2022. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://news.gallup.com/poll/389792/lgbt-identification-ticks-up.aspx

2. Turban J, Ferraiolo T, Martin A, Olezeski C. Ten things transgender and gender nonconforming youth want their doctors to know. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(4):275-277.

3. Bhattacharya N, Budge SL, Pantalone DW, Katz-Wise SL. Conceptualizing relationships among transgender and gender diverse youth and their caregivers. J Fam Psychol. 2021;35(5):595-605.

4. Keeley S. Integrative family therapy with transgender, gender diverse, and non-binary (TGDNB) young people. Aust N Z J Fam Ther. 2022;43(1):151-162.

5. Coolhart D, Shipman DL. Working toward family attunement: family therapy with transgender and gender-nonconforming children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(1):113-125.

6. Fey B, Ahola J, Casoy F. Treating family members of transgender and gender-nonconforming people: an interview with Eric Yarbrough, M.D. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2020;18(3):296-299.

7. Austin A, Craig SL, D’Souza S, McInroy LB. Suicidality among transgender youth: elucidating the role of interpersonal risk factors. J Interpers Violence. 2022;27(5-6):NP2696-NP2718.

8. Goldhammer H, Crall C, Keuroghlian AS. Distinguishing and addressing gender minority stress and borderline personality symptoms. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2019;27(5):317-325.

9. Sloan CA, Berke DS. Dialectical behavior therapy as a treatment option for complex cases of gender dysphoria. In: Kauth MR, Shipherd JC, eds. Adult Transgender Care: An Interdisciplinary Approach for Training Mental Health Professionals. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2018:123-139.

10. Johnsen C, Ding HT. Therapist self-disclosure of sexual orientation revisited: considerations with a case example. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2022.

11. Banerjee SC, Staley JM, Alexander K, et al. Encouraging patients to disclose their lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) status: oncology health care providers’ perspectives. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(4):918-927.

12. Acosta W, Qayyum Z, Turban JL, van Schalkwyk GI. Identify, engage, understand: supporting transgender youth in an inpatient psychiatric hospital. Psychiatr Q. 2019;90(3):601-612.

13. Brown JM, Naser SC, Brown Griffin C, et al. A multicultural, gender, and sexually diverse affirming school-based consultation framework. Psychol Sch. 2022;59(1):14-33.

14. Katz-Wise SL, Sansfaçon AP, Bogart LM, et al. Lessons from a community-based participatory research study with transgender and gender nonconforming youth and their families. Action Research. 2019;17(2):186-207.

15. Beischel WJ, Gauvin SEM, van Anders SM. “A little shiny gender breakthrough”: community understandings of gender euphoria. Int J Transgend Health. 2021;23(3):274-294.

16. Dhejne C, Van Vlerken R, Heylens G, Arcelus J. Mental health and gender dysphoria: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28(1):44-57.

17. Chumakov EM, Ashenbrenner YV, Petrova NN, et al. Anxiety and depression among transgender people: findings from a cross-sectional online survey in Russia. LGBT Health. 2021;8(6):412-419.

18. Wanta JW, Niforatos JD, Durbak E, et al. Mental health diagnoses among transgender patients in the clinical setting: an all-payer electronic health record study. Transgender Health. 2019;4(1):313-315.

19. Cardoso Silva D, Salati LR, Villas-Bôas AP, et al. Factors associated with ruminative thinking in individuals with gender dysphoria. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:602293.

20. Konrad M, Kostev K. Increased prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment and somatoform disorders in transsexual individuals. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:482-485.

21. Toomey RB, Syvertsen AK, Shramko M. Transgender adolescent suicide behavior. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20174218.

22. Abreu RL, Kenny MC. Cyberbullying and LGBTQ youth: a systematic literature review and recommendations for prevention and intervention. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2018;11(1):81-97.

23. Brown C, Porta CM, Eisenberg ME, et al. Family relationships and the health and well-being of transgender and gender-diverse youth: a critical review. LGBT Health. 2020;7(8):407-419.

24. Kosciw JG, Clark CM, Truong NL, Zongrone AD. The 2019 National School Climate Survey: the experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN. 2020. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://www.glsen.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/NSCS19-FullReport-032421-Web_0.pdf

25. Kulick A, Wernick LJ, Espinoza MAV, et al. Three strikes and you’re out: culture, facilities, and participation among LGBTQ youth in sports. Sport, Education and Society. 2018;24(9):939-953.

26. Waite S. Should I stay or should I go? Employment discrimination and workplace harassment against transgender and other minority employees in Canada’s Federal Public Service. J Homosex. 2021;68(11):1833-1859.

27. Reisner SL, Bailey Z, Sevelius J.Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S. Women Health. 2014;54(8):750-767.

28. Kattari SK, Bakko M, Hecht HK, Kattari L. Correlations between healthcare provider interactions and mental health among transgender and nonbinary adults. SSM Popul Health. 2019;10:100525.

29. Russell ST, Pollitt AM, Li G, Grossman AH. Chosen name use is linked to reduced depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicidal behavior among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(4):503-505.

30. Turban JL, King D, Kobe J, et al. Access to gender-affirming hormones during adolescence and mental health outcomes among transgender adults. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0261039.

31. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, et al. The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. 2016. Accessed October 3, 2022. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

32. Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, et al. Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sex Res Social Policy. 2018;15(1):48-59.

33. Turban JL, Kraschel KL, Cohen IG. Legislation to criminalize gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. JAMA. 2021;325(22):2251-2252.

34. Meyer IH. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2015;2(3):209-213.

35. Heise L, Greene MH, Opper N, et al; Gender Equality, Norms, and Health Steering Committee. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2440-2454.

36. Streed CG Jr, Beach LB, Caceres BA, et al; American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Hypertension; and Stroke Council.Assessing and addressing cardiovascular health in people who are transgender and gender diverse: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144(6):e136-e148.

37. Flentje A, Heck NC, Brennan JM, Meyer IH. The relationship between minority stress and biological outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2020;43(5):673-694.

38. Pellicane MJ, Ciesla JA. Associations between minority stress, depression, and suicidal ideation and attempts in transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;91:102113.

39. Glick JL, Lopez A, Pollock M, Theall KP. Housing insecurity and intersecting social determinants of health among transgender people in the USA: a targeted ethnography. Int J Transgend Health. 2020;21(3):337-349.

40. Bakko M, Kattari SK. Differential access to transgender inclusive insurance and healthcare in the United States: challenges to health across the life course. J Aging Soc Policy. 2021;33(1):67-81.

41. Connolly D, Gilchrist G. Prevalence and correlates of substance use among transgender adults: a systematic review. Addict Behav. 2020;111:106544.

42. Matsuno E, Israel T. Psychological interventions promoting resilience among transgender individuals: Transgender Resilience Intervention Model (TRIM). The Counseling Psychologist. 2018;46(5):632-655.

43. Reisner SL, Bradford J, Hopwood R, et al. Comprehensive transgender healthcare: the gender affirming clinical and public health model of Fenway Health. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):584-592.